Why China is building Africa’s railways

Origin: theB1m

Africa is undergoing a railway renaissance – and it’s being built in large part by China.

From Nairobi to Mombasa and Addis Ababa to Djibouti, China is financing, designing and constructing railways that are transforming Africa’s transportation infrastructure.

These megaprojects are more than just impressive feats of engineering, passing through safari camps and the East African desert.

They’re symbols of better connected societies, economic opportunity, international alliances, soft power, and a shifting balance in the world of construction.

To understand why China is building railways in Africa, you have to rewind a bit. We could go way back, but let’s start at the Bandung Conference in 1955.

Leaders from 29 Asian and African nations met in the hopes of working together in the wake of Western colonialism. From that international solidarity came the Tazara Railway, which opened in 1975.

“The railroad was financed and mostly built by China, and it provided the landlocked country of Zambia with a 1,860 kilometres link to Tanzania and the way to export its copper to the global market without crossing white minority ruled territories,” Associate Professor at NYU Shanghai Maria Adele Carrai said.

Since then, Chinese investment in Africa has exploded from about USD $75 million dollars in 2003, to roughly USD $2.7 billion in 2019. Now, more than 30% of China’s investment in Africa is in the construction sector.

“China has become the most important source of development finance in Africa,” Professor Carrai said. “In the past, we talked about railroad imperialism. But now nobody is really investing as much as China in this kind of railroad connectivity.”

China has built a massive high-speed rail network in a matter of years, and it’s now bringing its expertise to Africa.

Two of its biggest investments in East Africa are the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway and the Kenya Standard Gauge Railway.

The USD $4 billion Chinese-built line across Ethiopia stretches 756 kilometres from the landlocked capital of Addis Ababa to the port of Djibouti.

With commercial operations beginning in 2018, it’s now the backbone of the Ethiopian National Railway Network.

Construction involved modernising an old, deteriorated metre-gauge railway by upgrading it to the Chinese electrified railway standard, making it the first of its kind in East Africa.

The locomotives are supplied by Chinese contractors, and are built to withstand altitude differences of 2,000 metres, daytime temperatures of up to 50 degrees Celsius and cold nights.

One promise of the railway was to provide convenient, air-conditioned travel.

Passenger volumes haven’t been as high as expected, with only 84,000 people traveling in 2019, and the service isn’t always reliable. But a big part of the railway’s long-term potential is in freight transport.

More than 90% of Ethiopia’s international trade passes through Djibouti. And the new line carries roughly a quarter of all Ethiopian imports and exports. Still, freight volumes haven’t come close to reaching their full capacity yet.

Unsurprisingly, the railway is struggling to turn a profit.

70% of the project was funded using loans from China’s state-owned Eximbank. And in 2019, both passenger and cargo combined only brought in $40 million, well-below the $70 million cost of actually operating the line.

“The problem is if you don’t have freight or passengers that go through the railroad, then of course, you cannot generate enough income to repay the loans,” Professor Carrai said. “So this is kind of a vicious circle.”

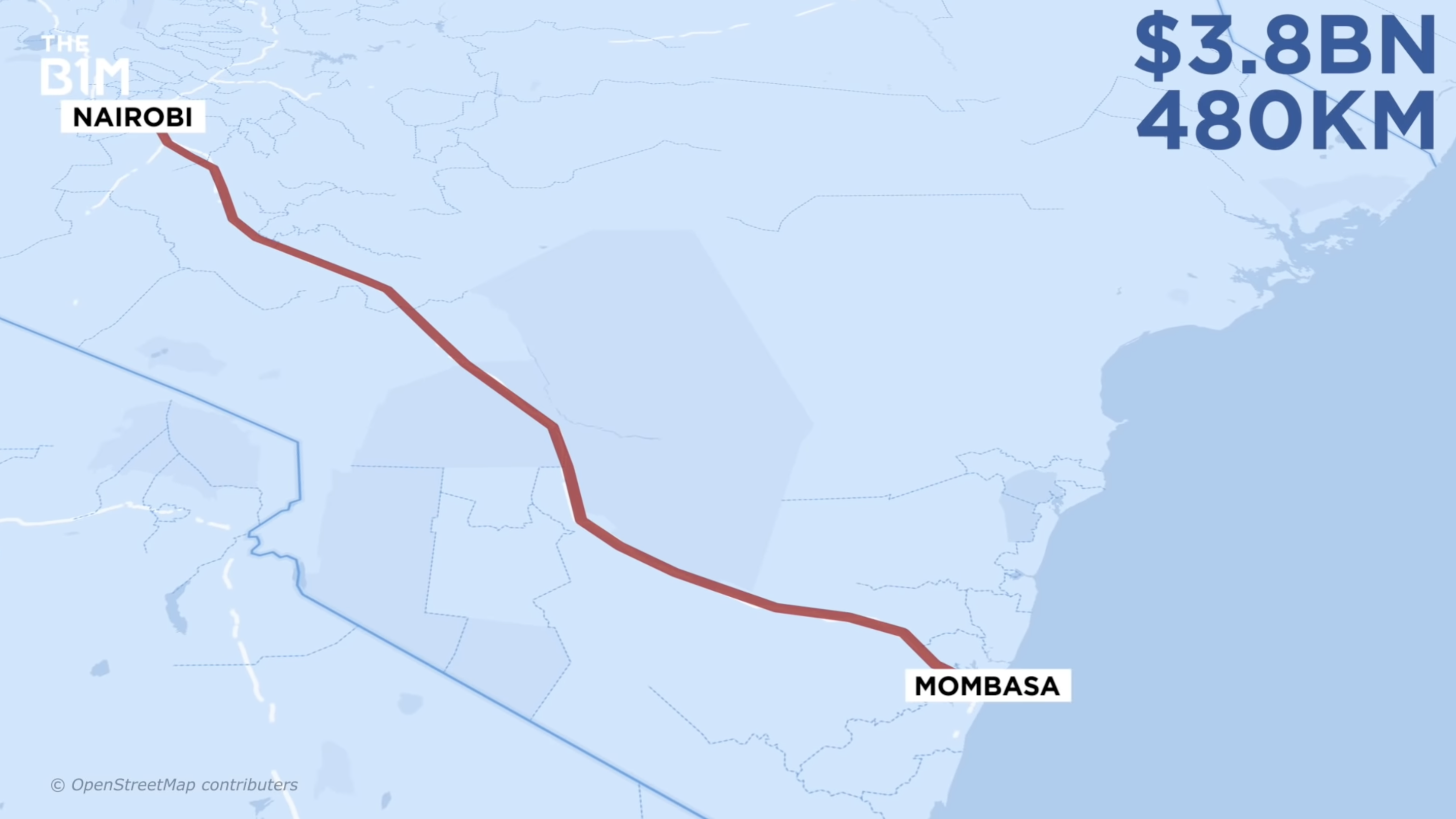

Over in Kenya, the Standard Gauge Railway opened in 2017.

With a route length of 480 kilometres, the USD $3.8 billion high-speed railway is Kenya’s largest infrastructure project since it gained independence in 1963.

Construction, led by China Road and Bridge Corporation, involved building long viaducts, deep cuttings and long embankments to navigate the rugged terrain along the route.

As you might expect, building a project of this scale through the stunning natural habitats Kenya is known for has proven to be a difficult balancing act.

Two sections of the railroad running through national parks faced protests from conservationists, over concerns it could threaten the wildlife. In response, designers added 14 wildlife channels and elevated sections of the track.

Now complete, the railway is a game changer for both trade and transportation in the region.

The passenger service has cut travel time from Mombasa to Nairobi from more than 10 hours, to roughly 5 hours with a $10 economy ticket. In its second year of service, the Kenyan railway transported 1.7 million passengers.

And the freight service ferried roughly 5 million tonnes of goods on Chinese-supplied locomotives.

“China’s approach to infrastructure development is attractive for African countries because China isn’t just providing the finance, it’s also the one stop shop that can supply everything for the lifecycle of a project.” PhD candidate at University of Cape Town Mandira Bagwandeen said.

“When dealing with China, things are simple. You don’t have to balance multiple actors’ interests or take them into consideration.”

But once again, things have gotten messy when it comes to money. China’s Eximbank financed 90% of the project, and now Kenya is struggling to pay back its loans.

And because both of these railways are built to a Chinese standard, any major upgrades or even parts that need to be replaced will have to come from China.

China’s investment in foreign infrastructure goes way beyond these railways.

Around the world, China is financing and constructing hundreds of infrastructure projects through its massive Belt and Road Initiative.

“Based on their own development experience, the Chinese are believers in the power of infrastructure and its ability to catalyze economic activity, so engaging with partners that have this appetite for infrastructure development works for Africa,” Bagwandeen said.

In Africa alone, China is estimated to have won almost half of all engineering procurement and construction contracts. But those contracts haven’t come without controversy.

The country has been accused of unfair labor practices in Africa, including bringing in its own workers instead of hiring locally.

Some studies have shown that Chinese firms actually do hire large numbers of local employees, but the top management positions are still dominated by Chinese employees.

The construction of the Ethiopian Railway employed roughly 20,000 local workers in Ethiopia and 5,000 in Djibouti.

That’s all to say, China’s involvement in African infrastructure is a complicated, nuanced investment. But relying so heavily on a single country to finance your development is a risky bet.

“You have Africa needing basic industrial infrastructure,” Bagwandeen said.

“African countries, not having the kind of financial war chest needed, and with Western lenders reluctant to invest in massive infrastructure, and the Chinese kind of coming in saying, ‘Not only can we provide the finance, but we can provide the skilled workers, we can provide the construction companies.’ You know, what option does Africa have?”

China’s revenue from construction projects in Africa skyrocketed from the early 2000s to now. But it’s dropped off a bit since around 2015.

While it’s not clear how long the money will keep flowing, China’s railways in Africa are laying the tracks for a long-term relationship between the two locations. If the partnership lasts, China’s railway legacy could stretch far beyond its own borders.