BUILDING A STRONG POST- PANDEMIC GHANAIAN ECONOMY THROUGH TRADE AND INVESTMENT WITH CHINA

Download this report here.

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

The 1955 Bandung Conference, where leaders from Egypt, Ethiopia, Libya, Sudan, and Liberia met their Chinese counterparts, is seminal to contemporary Africa-China engagements. Grounded by anti-imperialist imperatives, the relationship endured the turbulence of the Cold War geopolitics, the post-Soviet new order, the 1997 Asian crisis, and the 2008/09 great recession. Similarly, the relationship enjoyed reams of solidarity, including China’s support for building the TAZARA railway connecting Zambia’s copper belt to Dar-es-Salam1. In Africa. Indiana University Press., making it one of Africa’s most consequential legacy projects in decolonization. African countries reciprocated China’s gesture by casting the required votes to reinstate China into the United Nations following the advocacies of prominent African leaders. For instance, in his first major address to the UN General Assembly, Nkrumah contended that bringing China back to the fold was the right thing to do2.

Africa’s quest for total independence and China’s anti-colonial stance foreground continuing interactions during the 1960s and 1970s. China’s economy boomed during the 1990s, recording an unprecedented 10% annual growth. This remarkable growth translated into increased production and a search for more strategic sources of raw materials and markets for finished products3 . With plentiful resources amidst limited manufacturing, Africa became a preferred alternative. This geoeconomic orientation cupped a hitherto successful geopolitical period that ushered in a new era of engagement4. China expanded support for Africa, including infrastructure development, scholarships for African students, and capacity-building initiatives5, contributions African governments welcomed.

Furthermore, continuing structural adjustment policies imposed by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) during the 1980s hollowed and whittled away African states’ capacity to respond to crises6. The neoliberal benchmarks set by the Bretton Woods institutions, including reducing inflation, currency stabilization, and minimizing government involvement in economic activities, were achieved at the expense of massive poverty, crumbling public infrastructure, and widespread privatization of public assets7. Scholars contend that structural adjustment set back Africa’s development and upended its transformation for several decades8. Thus, Africa’s developmental challenges, the search for progress circumscribed by the African Union agenda 2063 initiative, and China’s quest to grow its economy dovetailed seamlessly, leading to deepened ‘all weather’ exchanges9.

Africa-China relations comprise material and nonmaterial exchanges such as development cooperation (aid), diplomatic support at multilateral levels, and security and military engagements10. These encounters were formalized in 2000 through the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) as the locus of diplomacy, economic, and development cooperation between Africa and China. The latest and eighth FOCAC summit, dubbed “Deepen China-Africa Partnership and Promote Sustainable Development to Build a China-Africa Community with a Shared Future in the New Era,”11 was organized in Dakar, Senegal in 2022.

Notwithstanding the opportunities, Africa-China relations face challenges. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic constitutes the most formidable puzzle for future Africa-China engagements. According to the United Nations World Economic Situation and Prospect 2022, Africa needs 6% growth from 2023 onwards to return to pre-pandemic status. This implies that Africa must more than double its current growth rate of 2.4% to meet this minimal target. This situation calls for more efforts and some invigoration of economic activities and possible strategic collaborations. Meanwhile, the minimal gains are being undermined by poor vaccination and production constraints. At the same time, China continues to face domestic employment and economic pressures.

In the face of the growing challenges, we ask: 1) How did both parties collaborate during the pandemic? 2) How do Africans perceive China as a development partner after the pandemic? 3) How did the disease impact Africa-China engagements? 4) What strategies and policies are in place to achieve trade and investment plans articulated by FOCAC VIII?

These questions are crucial because of the challenges posed by the pandemic and how they intertwine with the underbelly of underdevelopment and as determinants of how Africans experienced the pandemic. According to the 2022 UN World Economic Situation Report, Africa’s vulnerability is partially highlighted by having the world’s least vaccinated (8.6%) population. This, coupled with enduring structural constraints such as overreliance on raw material export, the predominance of informal economic activities, and poor integration into the global economy, triggered many doomsday predictions. Although not all the predictions have materialized, the evolution of the disease and the emergence of various variants is of considerable concern.

Africa’s engagements with China and the Western world show distinct patterns and strategies. Lessons from these experiences vis-à-vis pre-pandemic encounters are critical for building strong and resilient systems that inure to the continent’s needs and aspirations. This study fills part of this goal. Focusing on trade and investment plans of FOCAC VIII Action, we examine how African countries can harness their engagements with China for effective post-pandemic reconstruction. The research uses Ghana as a case study and argues that African countries desire investment and better terms of trade. However, the results will be more generative if enabled by structures and institutions that can absorb them. Considering the questions above, we assess the continent’s political economy in the context of a deliberate pursuit of structural transformation.

The rest of the paper is structured in nine parts. Part two describes the methodology, data collection techniques, and analysis. Part three discusses structural transformation to ground the analysis of trade and investment for post-pandemic reconstruction. Next, we examine Africa’s health systems and the impact of COVID-19. Part Five discusses the experiences of Africa and COVID-19 amidst the prediction of horror. Part six assesses Chinese trade and investment activities in Africa in the context of FOCAC VIII Action. Part seven analyses the perceptions of Ghanaians of China as a post-pandemic development partner. Part eight constitutes the report’s discussion, while part nine proffers some recommendations on how the proposals could be harnessed for post-pandemic reconstruction.

METHODS OF DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

Data for this study were collected using qualitative and quantitative techniques, including interviews, surveys, and a systematic literature review. Interviewees were purposively selected from Ghana, involving scholars, civil society organizations, and pan-Africanist agencies, to reflect the study’s scope. Thus, we sought audiences with the Ghana Investment Promotion Centre (GIPC), academics, Workers Unions, and the Ghana Union of Traders Association (GUTA). Extra efforts were made to organize meetings with the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning and the Ministry of Trade and Industry. However, our attempts yielded no dividend, as we were persistently stonewalled. We also contacted the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) secretariat without a response. We interacted with officials of China’s embassy in Accra using a question-and-answer format. Whenever possible, interviews were conducted in the offices of interviewees. Consent was obtained from all participants before any conversation took place. Participants were informed about the extent of their involvement in the study. They were informed about their right to pivot or halt interviews if they did not want to tow a given line of questioning. The interviews were electronically recorded, while notes were taken for analysis in NVIVO®.

| Value | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 141 | 57% |

| Female | 103 | 41% |

| Unwilling to disclose/ non-binary | 4 | 2% |

| Total | 249 | 100% |

We also conducted surveys to ascertain the perceptions of adult Ghanaians about Ghana-China interactions and how trade and investment could be leveraged to catalyze post-pandemic economic reconstruction. The surveys were administered in Greater Accra, Savannah, Northern, and Ashanti regions—four regions with varied Chinese activities in Ghana. We used KoboCollect® to design and administer the surveys between September 21, 2022, and September 28, 2022. After a week, 249 individual responses were collected, comprising 57% males, 41% females, and 1.89% nonbinary respondents (Table 1).

For the literature review, systematic searches used keywords such as COVID-19, Ghana, Africa, and China. The research was undertaken on Google Scholar and Academic Search Premier. We identified 162 papers, reports, book chapters, and newspaper publications. To ensure information credibility, we fact-checked each author’s credentials. Some papers were run through Connectedpapers.com to determine links to other refereed publications. At the end of this exercise, 22 papers were determined as relevant to the study and critically reviewed for this report.

Interview records were manually transcribed and imported into NVIVO® for thematic and content analysis, while secondary publications were coded thematically and analyzed. The surveys help us generate descriptive statistics and provide snapshots of the study’s variables.

Our study highlights the centrality of trade and investment as catalysts for building a dynamic post-COVID-19 economy in a structured manner. It also emphasizes bridging the knowledge gap in the African (Ghana)-China relationship despite both sides’ significant economic and political engagements. Finally, participants outline areas of investment and trade to pursue in post-pandemic reconstruction (Table 2).

| Value | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Technology/ skills transfer | 125 | 47.17 |

| Manufacturing | 97 | 36.6 |

| Infrastructure | 90 | 33.96 |

| Agriculture | 87 | 32.83 |

| Human resource development | 62 | 23.4 |

| Others… | 9 | 3.4 |

Table 2 shows that 125 (47.17%) of respondents recommend that there should be technology or skill transfer to support the Ghanaian economy. A range of 32% to 37% of the respondents also recommend that China, as a key partner towards Ghana’s post-COVID recovery, should focus on manufacturing, infrastructure, or agriculture. 62 (23.4%) recommend developing human resources, 9 (3.4%) provide other recommendations. We proffer some suggestions based on these findings to repurpose the relationship for better future cooperation.

RECONSIDERING STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATION

“In this fragile and uneven period of global recovery, the World Economic Situation and Prospects 2022 calls for better targeted and coordinated policy and financial measures at the national and international levels. The time is now to close the inequality gaps within and among countries. If we work in solidarity – as one human family – we can make 2022 a true year of recovery for people and economies alike.”

António Guterres, UN Secretary-General12

COVID-19 is still unraveling while its planetary impacts remain uncertain. However, in Africa, as elsewhere, inflationary pressures, commodity price hikes, and supply chain bottlenecks constitute a significant hurdle. These macro and microeconomic issues also link up and adversely affect health systems and care delivery across the continent. As the above epigram suggests, the entangled and interconnected nature of the various national economies requires holistic inquiry and a pragmatic approach in a post-pandemic reconstruction process. To attain this goal, we adopt economic transformation as a framework to investigate how trade and investments between Africa and China can be optimized to build stronger economies based on FOCAC VIII plans.

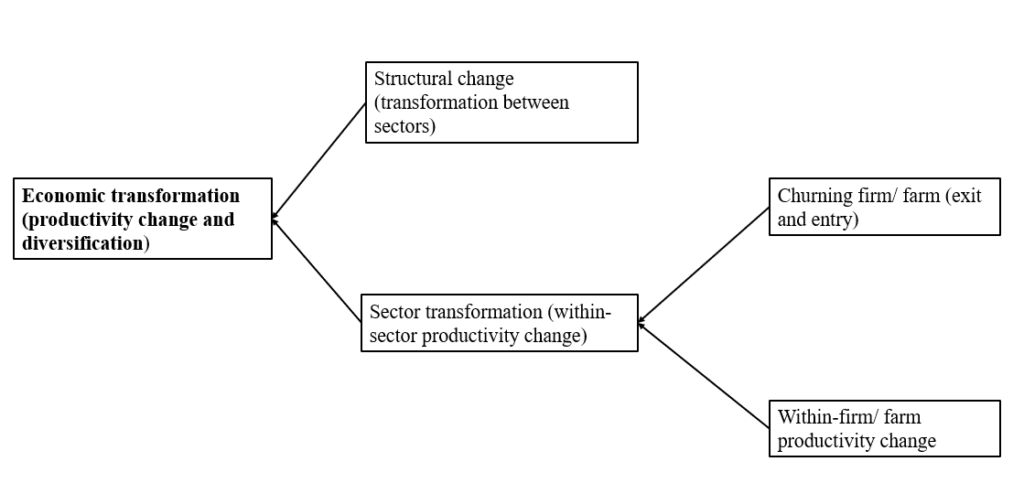

Source: adapted from Calabrese & Tang, (2023); Calabrese & Ubabukoh, (2020)

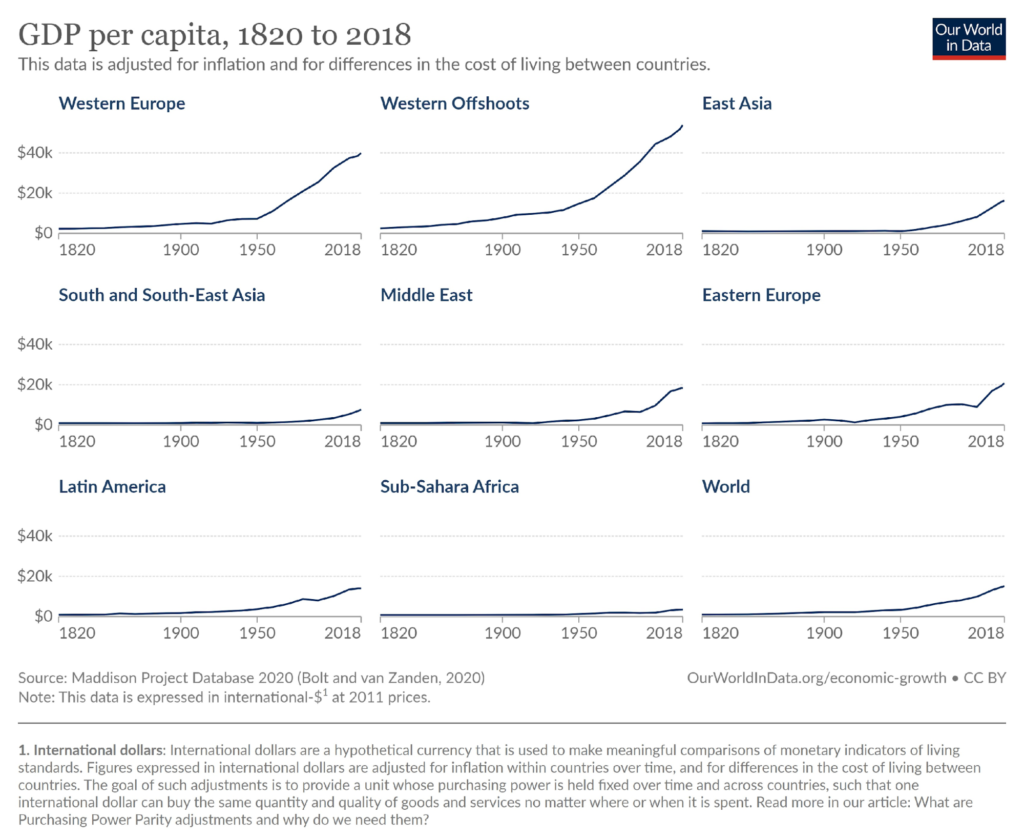

Africa’s underdevelopment predates COVID-19 as evidenced by the continent’s substantial economic transformation gap (Figure 2). Over the years, the continent’s economic performance has remained unimpressive13. While a few African economies have registered high gross domestic product (GDP) rates, most gains are derived from agriculture, which employs most of the productive labor force and the available capital but with minimal yields. Changing this outlook and building a resilient, inclusive, and diversified economy requires pragmatism.

Geographers, policymakers, and development experts deploy economic transformation to denote broad aggregate productivity change and economic diversification14. Thus, the concept implies resource transfer (reallocation) from low to high-productivity ventures. These shifts can occur within firms in a given sector (intra-sectoral) or between sectors or industries (inter-sectoral) (Figure 1). In the former, the changes entail moving labor and capital resources from peasant farming to commercial agriculture, while the latter encapsulates bolstering the productive capacity of manufacturing through innovations and research as opposed to agriculture investments15. Altering production outcomes transcend scales, entailing changes at the macro, meso, and micro levels.

Studies on economic transformation have tended to focus on explaining the pattern of successful and unsuccessful development instances. While findings vary by context, there is recognition of a “universal inverse association of income and the share of agriculture in income and employment”16. This implies that as countries evolve and advance economically, they have less productive labor in traditional fields such as agriculture than their income. At the same time, capital investment tends to yield more than what prevails elsewhere. Thus far, most of Africa presents the obverse, where most of the population is employed in agriculture and in the informal sector.

Despite Africa’s limited performance, structural transformation is neither a given nor the preserve of developed countries. It is a process driven by deliberate policies and initiatives. The purposiveness of structural transformation is exemplified by the experiences of the developmental states—countries that prioritize economic transformation17. Africa’s COVID-19 experiences, where lockdowns could not be enforced due to socioeconomic considerations and lack of capacity to manufacture or procure vaccines, have made pursuing structural change urgent. Post-pandemic reconstruction based on trade and investments coupled with strategic infrastructural investments can anchor Africa’s progress if the pathways can be customized and guided by suitable policies, as the UN Secretary-General had espoused.

AFRICA’S HEALTH SYSTEM

After weeks of uncertainties and anxiety, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a public health emergency of international concern on January 30, 2020. This news sought to draw attention, mobilize resources, and coordinate plans to combat the spread of the disease; subsequently, on March 11, 2020, WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic after it had swiftly spread to multiple countries. These actions spurred countries worldwide into taking measures to protect citizens.

With widespread economic disparities, concerns grew on how to tackle the disease and its rapid spread. Many developed countries rolled out myriads of social support and backed their scientists and public health professionals with the tools to fight the disease. In underdeveloped regions, limited resources, and fragile health systems broached concerns of a looming apocalypse. Melinda Gates’ April 10, 2020, interview on CNN18, stating the possibility of African streets being littered with bodies, encapsulates the imminent danger and horrifying spectacle.

Indeed, Africa’s health systems have been overstretched and burdened by communicable and non-communicable diseases before COVID-19. Diseases like malaria, HIV/AIDS, diabetes, cancer, and tuberculosis continue to pose significant concerns to Africans’ well-being. High maternal and infant mortalities compound this situation. Studies show that a child born in sub-Saharan Africa is 14 times more likely to die before age five than a child born in Europe and North America. Similarly, a child born in sub-Saharan Africa is ten times more likely to die in the first month than a child born in a high-income country19. Unfortunately, progressively decreasing health sector expenditure and investment have resulted in stressed health workers. For instance, although the continent accounts for about 22% of the global disease burden, it has only about 1% of global health expenditure and 3% of global health workers20. As such, it is common to see African health professionals migrating outside the continent for greener pastures and favorable working conditions.

WHO suggests 2.5 medical staff comprising doctors, nurses, and midwives per 1000 people to achieve primary adequate health care coverage21. Most African countries fall short of this threshold. In relatively wealthy African countries, the ratio of physician to patient runs from 1:450 to 1:1050, while in poorer ones, the ratio is from 1:15,000 to 1:62,000. Similarly, the continent’s critical and intensive care capacity remains strikingly low. The entire continent has about 20,000 beds in intensive care units. Additionally, ventilators are scarce throughout the continent. There are about 160,000 ventilators in the US, but 20,000 for the continent’s 1.3 billion people. Inequities, inaccessibility, and unaffordability of care exacerbate these conditions. In terms of medical supplies and medical essentials, the situation remains unchanged. Africa imports 94% of its pharmaceutical needs, leaving it at the vagaries of price fluctuations.

Beyond the concerns of the quality of health care, several socioeconomic and cultural hurdles compound the continent’s capacity to deal with diseases—about 71% of Africa’s active population works in the informal sector which is characterized by poor social services, insufficient turnovers, and limited savings. This means little safety net and fallback resources in cases of crisis like the pandemic for the continent’s majority. Additionally, about 56% of African urban dwellings are overcrowded or slums with inadequate critical amenities such as water and electricity. These factors compromise social distancing and handwashing measures prescribed by health experts. Furthermore, about 40% of African children are undernourished, thus predisposing them to several diseases. These factors are exacerbated by refugees who are poorly catered for across the continent22.

The preceding discussion underscores a severely constrained African health system. With this grim portrait, facing COVID-19 seemed daunting. The prospect of COVID-19, which wreaked havoc in developed countries, prompted the apocalyptic predictions in Melinda Gates’ CNN comments in fragile African health systems. Fortunately, none of the predictions came to pass. Instead, the continent’s disease management came to be regarded as a relative success. Given the limited resources and factors highlighted, some scholars even characterize it as creative and innovative.

AFRICA’S COVID-19 EXPERIENCE, RESPONSES, AND CHINA

At the time of writing, WHO has de-characterized COVID-19 as a global public health emergency as of mid-May 2023. At this time, the Africa CDC dashboard showed that 12,216,748 Africans were infected with the disease, of which 256,542 died and 11,517,411 recovered. The continent’s young demographic structure, rural livelihood, and exposure to previous pathogens and diseases such as Ebola and HIV/AIDS have been adduced as attenuating factors. What is fascinating about this account is that Africa’s underdevelopment attributes have become its savior! However, while these claims are essential, they accorded the continent a sense of passivity and sidestep the critical role of various governments.

On the contrary, research shows that decisive government actions and collective responsibility proved critical to tackling the pandemic23;24. Most African countries implemented lockdowns and social distancing measures with tact, grit, and purpose. In places like Eswatini (Swaziland), lockdowns were implemented before a single case was detected. Similarly, countries such as Rwanda, Senegal, and Tunisia created and utilized innovative and creative approaches to combating the disease25.

In Ghana, after detecting its first case on March 11, 2020, the government followed through with a three-week lockdown of Accra and Kumasi—the two biggest cities in the country. Similarly, schools were closed, and large gatherings such as funeral activities were banned. Also, mandatory mask-wearing in public places and physical distancing were instituted. Moreover, the complete closure of the country’s borders—sea, air, and land—underlined the government’s eagerness to tackle the disease.

The government’s strategy involved periodic presidential addresses to the nation carried live on major media outlets and social media platforms. To date, 29 such briefings have been made26. Some interviewees commended the government’s measures, especially the regular briefing, describing it as:

…good because in situations like that, much misinformation is spread if there is a vacuum. This vacuum is filled with these speeches by the president. They [speeches] calmed people down and showed that they [government] are in charge. They [speeches] provide updates and directions and offer people things to discuss rather than the propagandists taking over.

The speeches, which came to be famously called “Fellow Ghanaians,27” became the government’s main instrument for propagating strategies and approaches to tackling the disease. Following Amoah (2021), we categorize the government’s strategy into five approaches: The first three; testing, tracing, and treating/isolation. The fourth strategy entails ameliorating the socioeconomic hardship wrought by the disease on the citizenry. Fifthly, the need to shore up domestic industrial capacity to be self-reliant after COVID-19. These strategies dovetail with the tenets of economic transformation described above.

While laudable, limited domestic resources meant reliance on external support to accomplish the stated goals. Ghana is not a novice to external dependence and its accompanying conditionalities of liberalization, deregulation, and privatization. Some of these factors have accounted for the country’s present economic predicaments. Ghana has sought IMF assistance about 17 times with mixed results. On May 17th, 2023, the Fund approved US$3 billion to help the country tackle its deepening economic woes. The government claimed budgetary constraints induced by the pandemic precipitated the move. Beyond this, the country also accessed a US$1 billion rapid credit facility during the pandemic. This was supplemented with US$1.43 million from the World Bank and US$27.19 million from the African Development Bank28. The severity of the Ghanaian case even led to private donations by Chinese businessman Jack Ma.

With specific reference to Ghana, an interviewee stated that,

“…after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, China and Ghana united as brothers and supported each other. Ghana voiced its support for China at the first moment of the pandemic. China ardently helped Ghana to fight the virus by providing a large amount of anti-pandemic supplies. The first chartered flight containing anti-pandemic supplies donated by the Chinese government to Africa chose Ghana as its first destination.”

Furthermore, they described the China-Ghana friendship as having been consolidated by donations to “…the University of Ghana Medical Center, Greater Accra Regional Hospital, Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, and LEKMA Hospital. Provided diagnosis equipment to Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research through WHO, etc., and donated living and health supplies to the orphanage and women and children in the northern region with international organizations such as UNICEF.”

Subsequent collaborations involved material and nonmaterial exchanges29. The same interviewee further stated that China’s support for Africa was spearheaded by President Xi Jinping, whom they described as being, “…deeply concerned about the evolving COVID-19 situation in Africa. [And] called for holding the Extraordinary China-Africa Summit in June last year [2021], and made telephone conversation with 11 African leaders, which is a true testament to the special bond between China and Africa who reach out to each other during trying times.”

Other official documents and correspondence show that China donated vaccines, medical equipment, masks, and testing kits to various African countries throughout the pandemic. Additionally, China actively participated in the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative, signed debt suspension agreements, or reached a similar understanding with 19 African countries, and canceled interest-free loans due to mature by the end of 2020 for 15 African countries within the framework of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC)30. Although most African support towards China was nonmaterial, it is regarded as necessary. An interviewer noted that “China never forgets,” reiterating China’s appreciation of Africa’s support in whatever form.

Indeed, as an all-weather friend, Ghana-China relations was once again tested. Thus far, participants in this study claim the pandemic has provided moments to collaborate, strengthen, and renew engagement between both sides. FOCAC VIII’s emphasis on trade and investment seems to inspire that aspiration. As such, we posit that well-structured investment and trade between Africa and China will be crucial in changing and resourcing African health systems and stimulating economic growth and development in the post-pandemic era.

FOCAC VIII ACTION PLAN

Since FOCAC was institutionalized in 2000, eight summits have been organized with venues oscillating between China and Africa. Despite being hampered by COVID-19, the eighth conference took place in Dakar, Senegal, on the theme “Deepen China-Africa Partnership and Promote Sustainable Development to Build a China-African Community with Shared Future in the New Era.” Like the 2006 summit, which was hailed as monumental for attracting about 48 heads of state to Beijing and marking the golden jubilee anniversary of Africa-China relations, the 2021 summit generated its own headlines31;32.

For 2021- 2024, nine program areas were adopted, including healthcare, poverty reduction and agriculture development, green development, capacity building, cultural and people-to-people exchanges, peace and security cooperation, trade promotion, investment cooperation, and digital innovation.

Nevertheless, the challenges brought about by COVID-19 and the need for collaborations during and after the global health crisis using trade and investment opportunities were also emphasized. Trade and investment were fervently touted to facilitate the apparent shift from infrastructure. Our study collaborators emphasized trade and investment as critical in catalyzing post-COVID-19 reconstruction and, hence, economic transformation (see also Table 2). The following sections examine the plan’s specifics and possible pathways for engagement in building a more robust and resilient African economy.

HARNESSING INVESTMENT FOR ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION

China’s investments in Africa are crucial in promoting industrial development and integrating Africa into global and regional value chains. FOCAC VIII seeks to continue this trend by creating, encouraging, and supporting two-way investment opportunities. Re-emphasizing aspects of the 2021-24 action plan, one interviewee made copious references to the action indicating as follows:

China will encourage its businesses to invest no less than 10 billion US dollars in Africa in the next three years and establish a platform for China-Africa private investment promotion. China will undertake 10 industrialization and employment promotion projects for Africa, provide credit facilities of 10 billion US dollars to African financial institutions, support the development of African SMEs on a priority basis, and establish a China-Africa cross-border RMB center. China will exempt African LDCs [less developing countries] from debt incurred in the form of interest-free Chinese government loans due by the end of 2021. China is ready to channel to African countries 10 billion US dollars from its share of the IMF’s new allocation of Special Drawing Rights.

The China-Africa Development Fund and the China-Africa Fund for Industrial Cooperation will support Chinese investments in African firms and projects, including Public Private Partnerships. Practical cooperation in taxation will continue, with China supporting African countries to improve tax administration capacity. At the same time, efforts will be made to negotiate agreements on double taxation avoidance and resolve tax-related disputes.

The Chinese government also intends to regularly publish reports on Chinese investment in Africa to encourage more investment and support independent and sustainable development in Africa. Such a publication will help address the transparency issues that have engulfed Africa-China interactions. Table 3 summarizes the main areas of investment detailed in the Action Plan.

| Sector | Areas of Cooperation |

|---|---|

| Manufacturing | Investments in existing and new free trade zones, industrial parks, and green industrial parks |

| Agriculture | Expansion of investment in the agricultural sector |

| Green Economy | Investments in renewable energy projects and energy-efficient technologies |

| Digital Economy | Investments in digital infrastructure, telecommunications, and e-commerce platforms |

| Infrastructure | Investments in transportation networks, logistics, and critical infrastructure |

| Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) | Support for Chinese investments in African firms and projects, including PPPs |

| Taxation | Cooperation in improving tax collection and administration capacity |

Culled from FOCAC VIII Action Plan

Other study collaborators acknowledge the importance of foreign direct investment (FDI), especially that of China. Ghanaian Trade Union Congress (TUC) interviewees intone, “…yeah Chinese investments are good. They sometimes help expand certain aspects of the economy, especially areas some investors consider less profitable.” Similarly, some survey respondents indicate that “… Chinese businesses [especially China Malls] in Ghana help them obtain some goods cheaply as opposed to those sourced from other places.” This notwithstanding, GUTA members have a mixed view of Chinese investments in the country. The Association indicates that “…Chinese investments are good, but the authorities [Ghana government] have to ensure they [Chinese investors] do what they have been authorized to do.” They proposed effective monitoring by GIPC to close the loopholes in the system. These views by investment stakeholders underscore the dynamics of the sector in ensuring that appropriate steps can be adopted to maximize the proposed FOCAC VIII initiatives.

China is the leading source of investment in Africa, encompassing manufacturing, construction, financial services, and extractives33. For most people, increasing involvement in manufacturing could make Africa the next factory of the world, hence, transformation. Africa’s relative raw material advantage and Chinese domestic issues, such as tightening environmental regulatory frameworks, could push Chinese companies to Africa34. However, for Africa to optimize these opportunities, it needs policies to avert a race to the bottom as Chinese companies seek to expand their stake on the continent.

HARNESSING TRADE FOR ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION

A key talking point of the 2021 Action Plan is that China was to increase African imports. Table 4 summarizes the proposed areas of cooperation for Africa-China trade for 2021-2024.

| Sector | Summary |

|---|---|

| Trade Promotion and Exports | China supports African product promotion and exports to China through trade events and preferential measures. |

| Agriculture and Agro-products | China and Africa aim to improve the competitiveness of African agricultural products and integrate small-scale producers into formal networks. |

| E-commerce and Digital Trade | Both sides explore cooperation mechanisms, including e-commerce, to facilitate trade and simplify cross-border processes for African agro-products to China. |

| Imports from Africa | China plans to increase imports from Africa to US$300 billion in three years. |

| Geographical Indications and Value Addition | Efforts will be made to recognize African geographical indications and increase the value of African goods in the Chinese market. |

| E-commerce Hubs and Logistics | Exploration of establishing e-commerce hubs in Africa dedicated to exports to China and the development of trade corridors and logistics cooperation. |

Culled from FOCAC VIII Action Plan

GUTA officials indicate that trade relations between Ghana and China have worsened since the start of the pandemic, and they do not see any improvement in sight despite FOCAC VIII. This assessment was countered by another interviewee who observed that:

China is Ghana’s biggest trading partner and foreign investment source. In 2019, our [Ghana-China] bilateral trade volume was 7.46 billion USD, ranking among the top in Africa. The bilateral trade increased, not reduced, despite the pandemic. From 2013 to 2021, cumulative trade in goods between China and countries along the Belt and Road Initiative reached nearly 11 trillion US dollars; the two-way investment exceeded 230 billion US dollars. The China-invested airline company, power plant, steel company, and ceramic company significantly contribute to creating jobs and promoting developments in Ghana.

For GUTA, Ghana was not producing much during COVID-19, but the Chinese merchants and malls in the country remained well-stocked. For them, post-pandemic trade ties have to be structured so that Chinese malls [and investors] deal in high-end products [products not sold by Ghanaian traders] or form partnerships with Ghanaian traders to pursue mutual benefits.

The trade partnership between China and Africa remains solid. In 2018, US$5 billion was committed to facilitating exporting African (agricultural) produce and services. This figure doubled in 2021. As the preceding years suggest, the prospects of using trade to rebuild resilient economies after COVID-19 remains promising. This is because whilst many have argued that Africa’s manufacturing is being significantly hampered by growing dependence on Chinese import and, thus, a need to curtail Chinese import as a strategy to breed live into African industrialisation, the evidence especially during the COVID induced supply chain disruption indicates that such approach will be catastrophic if not done strategically. Specifically, Haugen and Obeng35 illustrates how economic lives in Ghana and China have become so profoundly intertwined that indiscriminate decoupling is neither possible nor desirable. They further argue that although the supply chain disruptions from China initially led to the substitution of certain products previously imported from China, and the effects partially sustained after the COVID-induced barriers to imports from China were removed, the disruptions were also costly for many Ghanaian producers, as they depended on Chinese intermediary products, tools, and other inputs in order to sustain these gains.

Indeed, trade exchanges remain pivotal to Africa-China engagements beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. These ties are bound to continue with China set to increase the import of African (agricultural) produce. In that regard, efforts are being made to improve the competitiveness of African agricultural products and facilitate the integration of small-scale producers into formal processing and distribution networks. Furthermore, China and Africa are exploring cooperation mechanisms, including establishing e-commerce hubs in Africa dedicated to African exports to enhance trade facilitation and promote paperless cross-border trade. Emphasis is on simplifying processes for African agro-products through e-commerce platforms.

As noted above, China pledged to offer US$10 billion in trade finance to support African exports. Additionally, China plans to establish a pioneering zone for China-Africa trade and economic cooperation and a China-Africa industrial park for Belt and Road cooperation. Finally, both sides support the development of marine-rail-combined transportation, such as the “Sichuan-Europe-Africa Service,” to create new trade corridors and enhance logistics cooperation between China and Africa. The hope is that these efforts would help address some of the glaring issues in Africa-China trade relations, namely the trade imbalance and the poor terms of trade with Africa, the rising cost of freight to contribute to Africa’s post-COVID structural transformation.

Trade has been a central feature of Africa-China engagements and continues to be widely studied by many scholars. Predominantly, the modality entails China importing commodities and raw materials from Africa while exporting manufactured and finished products. The current arrangement has resulted in a staggering deficit of US$17.7 billion since 2019, soaring to US$41.5 billion in 202036. Inference can be made that the running deficit underpins the need to shore up African imports to US$300 billion by 2024, thus a 27.3% expansion of the current US$72.7 billion African trade volume. Africa-China trade arrangements are undoubtedly conditioned by the so-called comparative advantage and other domestic factors, which have persisted until now. Comparative advantage deindustrializes, making African companies less competitive domestically and internationally. The structure also perpetuates Africa as a raw material exporter, hence, underdevelopment. Continuous trade with China should prioritize changing this structure to promote economic transformation by considering the recommendations below.

Analysis of Ghana-China investment and trade engagements reveals some poignant lessons that both Africa and China can learn from to enhance post-pandemic relations. We draw insights from two recent landmark Ghana-China investment and trade deals: the 2010 US$3 billion China Development Bank (CDB) loan to finance urgently needed gas projects and the 2018 Master Project Support Agreement between the Ghanaian government and Chinese state-owned Sinohydro Corp Limited.

The 2010 US$3 billion deal was mainly secured to assist Ghana in financing the construction of urgently needed gas projects to enable the country to position itself as an oil producer37;38. As a non-concessional loan, the arrangement was meant to help Ghana access funds it would have ordinarily failed to secure based on its international financial outlook at the time. Likewise, the Sinohydro presented an unconventional barter-like (resource swap deal) trade deal where the country will get US$2 billion worth of infrastructure39.

These two innovative and somewhat novel deals strategically and seamlessly integrated investment and trade, leveraging the country’s natural resources rather than its foreign reserves and existing credit ratings. China’s willingness to assist Ghana and to explore what some described as new terrains remains remarkable and applaudable. These non-concessional loan deals sought to look internally to build urgently needed infrastructure to position Ghana as an exporter of refined oil and bauxite but faced some challenges.

| 2010 China Development Bank Loan | 2018 Master Project Agreement |

|---|---|

| Signed under President Evans Atta Mills’ (National Democratic Congress) administration. | Signed under President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo Addo’s (New Patriotic Party) administration. |

| Did not receive support from the opposition (No consensus). | Failed to garner support from the opposition (No consensus). |

| Delay in the release of funds by the Chinese institution. | Delays affected some project timelines. |

| Minimal involvement of existing government and civil society structures. | Massive backlash from civil society organizations and incoherent government involvement. |

A careful study suggests that internal mechanisms and agency on the part of Ghana were highly responsible for the outcomes. The two administrations could have done a better job at building consensus and effectively coordinating existing and new state agencies to facilitate the processes from their planning stages to completion. While these projects come as urgent and requiring immediate action, efficiency and due diligence should not be sacrificed. We however posit that African countries should be encouraged to brainstorm more innovative deals irrespective of the challenges. As African countries engage their Chinese counterparts in developing and designing tailor-made investment and trade deals that leverage Africa’s resources to reshape financing its projects among others, the continent could use the opportunity to strengthen its internal structures and systems to ensure better outcomes. To enhance Africa’s credibility to attract the support of friends like China, intentional collaboration, accountability, and broad consultation within and among African countries, Regional Economic Communities (RECS), and civil society organizations are needed. These measures could ensure coherent and comprehensive deals that guarantee win-win outcomes. The recent Zambia-China debt restructuring bolsters this claim40.

CLOSING THE KNOWLEDGE GAP IN AFRICA-CHINA RELATIONS

The foregoing highlights the depth of Africa-China engagements before and during the pandemic. Unfortunately, not much is known by the majority about this growing encounter. Post-pandemic cooperation requires trust. As such, how Africans perceive engagement with China would be critical in building mutual respect and trust. Our findings (Figures 3, 4, and Table 6) demonstrate a significant gulf in how Ghanaians view Chinese activities. Despite growing trade and investment ties, many Ghanaians are uninformed or misinformed about the Ghana-China partnership, let alone their economic and political collaborations. To some of our respondents, China-Ghana bilateral relations are windows for gauging engagement with other African countries. If this conception holds, stakeholders should reflect critically on the results below.

This figure suggests that less than a quarter of the respondents have an in-depth knowledge of the role of China in Ghana’s development, underscoring the urgent need to bolster capacity across the continent. Institutions such as the Afro-Sino Centre for International Relations (ASCIR) and other Think Tank formations are germane here. Moreover, the survey shows that 55.09% of the respondents knew nothing about China’s COVID-19 support for Ghana, although both sides supported each other, as indicated earlier.

| Value | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Media (radio, TV, print media) | 154 | 58.11 |

| Social media (Facebook, Twitter, Tik Tok, Instagram) | 137 | 51.7 |

| Ghanaian government sources (policy briefs) | 54 | 20.38 |

| Academic/ published articles | 47 | 17.74 |

| Policy think tanks, CSOs, or NGOs | 28 | 10.57 |

| Chinese authorities and media outlets | 10 | 3.77 |

| Others | 12 | 4.53 |

Table 6 shows that over half of the respondents got information about Ghana-China engagements through traditional and social media. 154 (58.11%) and 137 (51.7%) respondents were found in the traditional and social media categories respectively. 54 (20.38%) respondents relied on government sources, while a small minority of 10 (3.77%) had information from Chinese authorities and media outlets. In the age of pervasive disinformation, accurate information would be essential in disseminating issues concerning growing Africa-China ties.

Figure 5 above does not give a very positive outlook of China’s relationship with Ghana. Apart from the fact that 27.55% of the respondents were not sure of how to rate China’s development partnership with Ghana compared with other countries and institutions, the second highest percentage (25.28%) think that Ghana’s engagement with other countries is superior to that of China. 14.34% of the respondents were categorical indicating that China’s development partnership with Ghana is bad. 23.10% of respondents deemed China engagement with Ghana as superior. Compared to previous years, China’s outlook overall, on the continent and in Ghana is growing positively.

A breakdown of Chinese perception across the regions in our survey data, where mining activities and Chinese involvement in illegal mining was less prevalent, respondents viewed China more positively than other partners. In the Northern Region, where the menace of illegal mining was less prevalent, survey respondents focused on the construction of the first ultramodern sports stadium completed in 2008 by the Shanghai Construction Group of China as well as the maiden interchange constructed as part of the US$2 billion China Sinohydro deal. Moreover, they emphasized Chinese trade and investment in the region, particularly in the assembling and selling of motorbikes. The Northern Region scenario illustrates how some of GUTA’s concerns can be addressed. The Chinese firms in the region engage in assembling motorbikes in plants located within the region and not in the retail of the motorbikes. They train Ghanaians to assemble the bikes and support Ghanaian merchants in the retail.

Survey participants from the Northern region were more inclined to indicate that they knew people who had benefitted from Chinese investment and trade. They were also more likely to indicate that they know relatives or friends who have benefitted from Chinese skills and knowledge transfer. They were also more likely to indicate that they have benefitted directly from Chinese products, mainly motorbikes and mobile phones. It is worth noting that motorbikes constitute a significant mode of transportation in the Northern Regions of Ghana. In addition, mobile phones are not merely used as personal communication devices but as tools for business, especially Mobile Money (MoMo) transactions like MPESA in Kenya.

DISCUSSIONS

Africa-China engagements have grown and matured over the years, a fact reflected by the growing willingness of both sides to openly discuss traditionally sensitive issues such as debt and trade imbalances. At FOCAC VIII, many African leaders called for better engagements with Beijing across multiple sectors, including trade and investment. These pushbacks are imperative and align with our argument on the centrality of trade and investment in building a resilient economy in post-COVID-19 Africa and helping it achieve its structural transformation.

Indeed, Chinese officials are also receptive to the issues raised in open discussions with African leaders. They also often propose corrective measures to address the issues of mutual concern. In response to the calls for rectifying the partnership and rebalancing trade between China and Africa at the 2021 FOCAC, for example, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced an additional US$10 billion in private investment over the next few years while also noting that African exports, especially agricultural products, would benefit from customs exemptions. Indeed, the Chinese leader set a target of US$300 million in African imports within three years. Thus, a 27.3% increment of the current trade value. Policies, strategies, and implementation will decide whether the trade deficit gap can be closed sooner or later.

Though not with as much extravagance as it used to be a few years ago, China intends to keep being active in the structural transformation of Africa’s economy. Enhanced Chinese investment on the continent is key to that. China is known for aiding Africa in infrastructure projects, including power plants and urban railways. China has also long expanded support for Africa beyond infrastructure projects, including scholarships for African students and capacity-building initiatives. The two-way traffic generally benefits both sides: China accrues soft power and gains access to Africa’s resources and youthful market, while Africa relies on China’s support for its development efforts. In that regard, China’s contribution is welcomed in Africa, especially by African governments.

| Statement | Frequency | Percentage |

| China’s activities in Ghana are a threat to Ghanaian entrepreneurs and industries | 100 | 37.74 |

| There is a general trade deficit in favor of China | 69 | 26.04 |

| Nothing, I think it is going well | 55 | 20.75 |

| The price of Chinese goods is affecting consumers | 33 | 12.45 |

| Others | 20 | 7.55 |

We have thus far explored how African countries can harness their engagements with China for post-pandemic reconstruction efforts by focusing on the two-way interactions regarding trade and investment as articulated in the FOCAC VIII Action Plan. Focusing on Ghana, we argue that Africa needs better terms of trade and investment. Also needed are the infrastructures and institutions to enable and absorb the efforts to structurally transform Africa. These claims bestow responsibility on Africa as well as China. While African countries have to strategically identify areas of investment partnerships and retool their existing institutions to deliver the goods, China should ensure that their terms of trade are favorable to generate win-win outcomes. At the same time, Chinese investments should prioritize forming joint partnerships with Africa to promote skills and technology transfers. Africa’s poor economic performance and limited structural transformation are reversible. These conclusions stem from the conviction that strategic investment and better Africa-China trade and investments will be crucial in forging Africa’s transformation and stimulating economic growth and development in the post-pandemic era.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the preceding, we propose the following recommendations to guide the post-COVID reconstruction of African economies leveraging trade and investment ties with China.

- Africa has a running infrastructure deficit exceeding US$150 billion. Infrastructural provision is fundamental to achieving the plans outlined in the 2021 action plan and the operationalization of AfCFTA. Infrastructure should not be an appendage, as seen in the recent action plan, but a critical undertaking designed to fill the gaps across the continent. Both sides should reconsider infrastructural investment and work collaboratively to reinstate the initiative in future action plans. Adequate infrastructural finance portends long-term transformative impacts with win-win outcomes for both sides, akin to the structural transformation proposed in this study.

- African countries should encourage and support vigorous indigenous capital formation and accumulation. This means individual countries should assess their needs and design appropriate industrial policies to achieve them. A critical mass of indigenous entrepreneurs would appropriate skills transfer and partnership formations with Chinese businesses and ensure long-term prosperity and the fight against capital flight from the continent.

- Strengthen investment laws and clarify what counts as investment. Investors need clarity on what counts as investment or otherwise. In Ghana, GIPC’s strategy of licensing investors without adequately checking the capacity to honor minimum fiscal requirements is problematic and inadvertently creates tensions between local and foreign investors. Peace and tranquillity are required to forge partnerships between local and external investors and ensure skills and technology transfer.

- Investment plans should be assessed for their potential contributions and connections with other sectors of the economy. This means each country should develop long and short-term development plans to tailor FOCAC action plans to build an articulated economy. Without such a framework, even the best plans would yield minimal results. For long-term economic transformation to occur, plans must be articulated with a clear blueprint to evaluate their output effectively. This idea chimes with the need for capacity building, which should be pursued intentionally.

- African governments should prioritize removing the bottlenecks investors encounter in their operations. This should be done to promote and boost domestic and external investments. Issues of corruption and administrative red tape should be taken seriously. Individual/investor complaints should be acted on swiftly, and the outcome should be communicated to the affected parties transparently. Also, governments should resource existing institutions/establish new ones to coordinate activities in strategic areas of the economy. Thus, governments should intentionally resolve and ease domestic investors’ drudgery to promote equity. The broad-brush approach existing in most countries needs serious reconsideration.

- African governments could seek joint ventures in technology-related investments to link up with other sectors of African economies, especially agriculture. There would be no structural transformation, including industrialization and manufacturing, if agricultural activities were neglected.

- Both sides need to work collaboratively to address the current convertibility issues. African countries use different currencies in their dealings with China. The current system of multiple conversions is avoidable. The African and Asian Development Banks can be consulted on how to work out a standard system to enhance the terms of trade between China and Africa without losing much transaction value.

- Exploration of the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS), as well as China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), promises to hold solutions to financial integration, which is needed to enhance both intra-African trade and Africa’s trade with key partners like China. These payment systems, if leveraged, could also significantly address the issues of illicit trade and, consequently, illicit financial flows that have characterized Africa’s large cash-based and informal economy. Investments in Africa will fail to yield the anticipated outcomes if money laundering and illicit financial flows remain prevalent. Efforts to harness investment for economic transformation should include mechanisms and systems to support Africa’s financial institutions and investigative agencies with resources and expertise to tackle these loopholes effectively and efficiently.

- African governments could work to increase import of Chinese capital goods, such as technology, machinery, and equipment, with available spare parts and trained technicians to help boost manufacturing capacity on the continent. African governments could use commodity revenues to diversify current economies to reduce overreliance on commodity exports.

- African governments need to ensure industrial upgrades by incentivizing existing entrepreneurs/firms. Government support of market research in identifying niche investment areas is crucial for long-term advancement.

- Both sides need to cooperate in building trust amongst citizens and build trust for vibrant post-pandemic engagements.

REFERENCES

- Monson, J. (2009). Africa’s Freedom Railway. In Africa. Indiana University Press. ↩︎

- Chau, D. C. (2007). Assistance of a Different Kind: Chinese Political Warfare in Ghana, 1958–1966. Comparative Strategy, 26(March 2015), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/01495930701341610 ↩︎

- Tull, D. M. (2006). China’s engagement in Africa: scope, significance and consequences. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 44(03), 459–479. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X06001856 ↩︎

- Mohan, G., & Power, M. (2009). Africa, China and the ’new’economic geography of development. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 30(1), 24–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9493.2008.00352.x ↩︎

- Benabdallah, L. (2020). Shaping the Future of Power: Knowledge Production and Network-Building in China-Africa Relations. University of Michigan Press. ↩︎

- Amoah, L. G. A. (2021). COVID-19 and the state in Africa: The state is dead, long live the state. Administrative Theory and Praxis, 43(3), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2020.1840902 ↩︎

- Apugisah, A. A. (2012). On Ghanaian development: technical versus street evidence. In H. Lauer & K. Anyidoho (Eds.), Reclaiming the Human Sciences and Humanites through African perspectives: Vol. I (pp. 388–412). Sub-Saharan Publishers. ↩︎

- Owusu, F., & Samatar, A. I. (1997). Industrial Strategy and the African State : The Botswana Experience. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 3968(March). ↩︎

- Zajontz, T. (2022). “Win-win” contested: negotiating the privatisation of Africa’s Freedom Railway with the “Chinese of today.” Journal of Modern African Studies, 60(1), 111–134. ↩︎

- Benabdallah, L. (2020). Shaping the Future of Power: Knowledge Producution and Network-Building in China-Africa Relations. University of Michigan Press. ↩︎

- https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjb_663304/zwjg_665342/zwbd_665378/202111/t20211127_10454129.html ↩︎

- https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjb_663304/zwjg_665342/zwbd_665378/202111/t20211127_10454129.html ↩︎

- Arthur, P. (2007). Development institutions and small-scale enterprises in Ghana. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 25(3), 417–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589000701662418 ↩︎

- Whitfield, L., Therkildsen, O., Buur, L., & Kj, A. M. (2015). The Politics of African Industrial Policy: A Comparative Perspective. Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

- Calabrese, L., & Tang, X. (2023). Economic transformation in Africa: What is the role of Chinese firms? In Journal of International Development (Vol. 35, Issue 1, pp. 43–64). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3664 ↩︎

- Calabrese, L., & Ubabukoh, C. (2020). Innovation and economic transformation in low-income countries : a new body of evidence (Issue February) ↩︎

- Mkandawire, Thandika. (2001). Thinking about developmental states in Africa. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 25(3), 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/25.3.289 ↩︎

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qSVse07y2O4&ab_channel=CNN ↩︎

- https://prame.openum.ca/files/sites/230/2023/06/working-paper_EN_digital.pdf ↩︎

- Oppong, J. R. (2020). The African COVID-19 anomaly. African Geographical Review, 39(3), 282–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2020.1794918 ↩︎

- Oppong, J. R., Dadson, Y. A., & Ansah, H. (2022). Africa’s innovation and creative response to COVID-19. African Geographical Review, 41(3), 318–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2021.1897635 ↩︎

- Oppong, J. R., Dadson, Y. A., & Ansah, H. (2022). Africa’s innovation and creative response to COVID-19. African Geographical Review, 41(3), 318–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2021.1897635 ↩︎

- Amoah, L. G. A. (2021). COVID-19 and the state in Africa: The state is dead, long live the state. Administrative Theory and Praxis, 43(3), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2020.1840902 ↩︎

- Oppong, J. R. (2020). The African COVID-19 anomaly. African Geographical Review, 39(3), 282–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2020.1794918 ↩︎

- Oppong, J. R., Dadson, Y. A., & Ansah, H. (2022). Africa’s innovation and creative response to COVID-19. African Geographical Review, 41(3), 318–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2021.1897635 ↩︎

- The latest speech was made on May 28, 2023, (https://presidency.gov.gh/index.php/briefing-room/speeches/2415-address-by-the-president-akufo-addo-on-updates-to-ghana-s-enhanced-response-to-the-coronavirus-pandemic) ↩︎

- The president has consistently opened his address to the nation by saying Fellow Ghanaians ↩︎

- COVID-19 AND BEYOND | African Development Bank Group – Making a Difference (afdb.org) ↩︎

- Fei, D. (2022). Assembling Chinese health engagement in Africa: structures, strategies and emerging patterns. Third World Quarterly, 0(0), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2022.2042802 ↩︎

- Bagwandeen, M., Edyegu, C., & Otele, O. M. (2023). African agency, COVID-19 and debt renegotiations with China. South African Journal of International Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2023.2180083 ↩︎

- Adovor Tsikudo, K. (2023). Different approach, same focus: How China is shaping the future of its African cooperation through education. Human Geography, 194277862311736. https://doi.org/10.1177/19427786231173626 ↩︎

- Alden, C. (2007). China in Africa: African Arguments. Zed Books. ↩︎

- Tang, X. (2018). Geese Flying to Ghana? A Case Study of the Impact of Chinese Investments on Africa’s Manufacturing Sector. Journal of Contemporary China, 27(114), 924–941. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1488106 ↩︎

- Hensengerth, O. (2013). Chinese hydropower companies and environmental norms in countries of the global South: The involvement of Sinohydro in Ghana’s Bui Dam. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 15(2), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-012-9410-4 ↩︎

- Haugen H. O & Obeng M.K.M (2024) .Supply-chain Disruptions under COVID: A Window of Opportunity for Local Producers?. Forum for Development Studies, DOI: 10.1080/08039410.2024.2302999 ↩︎

- https://www.brookings.edu/articles/focac-2021-chinas-retrenchment-from-africa/ ↩︎

- Mohan, G. (2015). Queuing up for Africa: the geoeconomics of Africa’s growth and the politics of African agency. International Development Planning Review, 37(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2015.5 ↩︎

- Rupp, S. (2013). Studies Review : Ghana , China , and the Politics of Energy Ghana , China , and the Politics of Energy. African Studies Review, 56(01), 103–130. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2013.8 ↩︎

- Amoah, L. 2020. Five Ghanaian Presidents and China: Patterns, Pitfalls, and Possibilities. University Legon: Ghana Printing Press ↩︎

- Bagwandeen, M., Edyegu, C., & Otele, O. M. (2023). African agency, COVID-19 and debt renegotiations with China. South African Journal of International Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2023.2180083 ↩︎